Digital Competencies in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and Algorithms (Toolkit)

As individuals born into and living in the twenty-first century, we share a common language. Unlike other languages we possess (such as Turkish, English, German, French, etc.), this language was not developed for communication between humans. We developed it for machines to communicate with one another.

The alphabet of this language consists of only two letters: 1 and 0. For this reason, machine language—also referred to as the binary system—is in fact merely a low-level programming language. Although we initially developed this language to enable machines to communicate and transfer data quickly and consistently, we are now living in a society shaped upon this binary system.

A significant portion of our daily lives is spent producing or consuming content that travels in the form of 1s and 0s. Moreover, we now strive not only to communicate with one another through machines or to allow machines to talk to each other, but to communicate directly with the machines themselves.

Of course, we don’t entirely set aside the thousands of years of written heritage or alphabets that allow us to express ourselves as humans and try to express every thought using just 1s and 0s. Instead, thanks to advances in computer technology—especially in processor performance—we build an “intermediary” layer between machine language and our own language.

With the help of advancements in the field of natural language processing (NLP) and the subsequent emergence of large language models (LLMs), we now communicate with machines by speaking human language.

Ultimately, communicating with machines (in its simplest form, performing any operation on a computer) is not a new concept. For years, we have performed tasks by selecting useful options from applications created by developers who know various programming languages.

What is new and different is that we now have tools that allow us to create our own unique programs by simply speaking our own language—without needing to know machine language or any programming language at all. Thanks to NLP and LLMs, these tools—commonly referred to as artificial intelligence—understand human language and generate responses comprehensible to humans by leveraging the massive datasets they are trained on.

To benefit from these new and “intelligent” tools of the digital world, it is not only necessary to have basic digital skills, but also to understand the potential, usage areas, methods, and limitations of these tools.

This guide and toolkit were designed as a starting point to help you acquire the competencies needed in the age of artificial intelligence and algorithms.

Throughout this guide, you will learn about social capital and its relationship with digital environments, the twin transition, digital competencies, current risks and trends, and digital literacy in the age of artificial intelligence and algorithms.

Becoming Digitally Literate in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and Algorithms

Although the term artificial intelligence began to enter most of our lives in the 2020s, as a concept it dates back to ancient times, and as a term, it originates from a 1956 workshop organized by John McCarthy and his team [3]. The developments that brought artificial intelligence to its current state include advancements in semiconductors (i.e., microprocessors), technologies that facilitate and accelerate the digital storage of data, and deep learning—a machine learning technique.

Artificial intelligence, which is essentially a subfield of applied computer sciences, has become a strategic technology that demonstrates powerful abilities in learning, reasoning, and planning, leading the global technological revolution and industrial change. In fact, many countries have designated the development of artificial intelligence as a national strategy to increase international competitiveness and ensure national security [4].

As its strategic importance and the investments in this area indicate, training an AI model and developing new language models is too complex to be taught in this guide; it requires expertise, powerful hardware, and significant funding.

Therefore, while this guide cannot teach you how to develop your own AI model, it does address the development steps of these models, the data they are trained on, and the current pitfalls that should not be overlooked.

Because being digitally literate in the age of algorithms requires not only mastering the skills outlined in the digital competence framework we will cover below, but also the qualified and ethical use of AI tools.

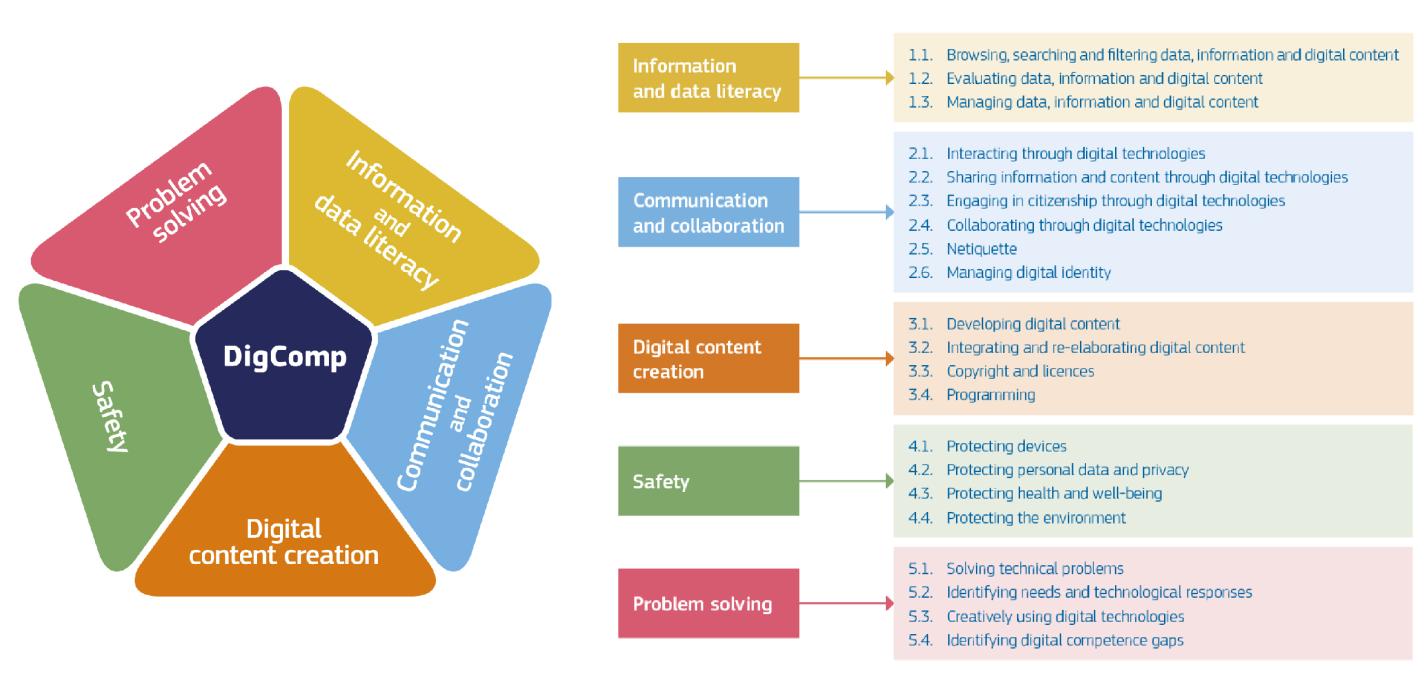

European Digital Competence Framework (DigComp 2.2)

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens, commonly known as DigComp, serves as a fundamental reference source for digital competences. For this reason, this guide is also built upon that framework. In DigComp, digital competence is defined as the confident, critical, and responsible use of digital technologies for participation in society, work, and learning. These competences are also part of the Key Competences for Lifelong Learning.

DigComp defines twenty-one distinct competences within five competence areas. Each competence is measured across eight proficiency levels [5]. Let’s first review these five areas:

- Information and data literacy

- Communication and collaboration

- Digital content creation

- Safety

- Problem solving

Information and data literacy is a competence that can be associated with media literacy, which emerged with the proliferation of mass media and their role in helping large audiences access information and news. However, today, not only newspapers, radio, or television but also the internet—which encompasses and expands all these tools—requires a different skill set. The “Information and data literacy” area covers browsing, searching, and filtering data, information, and digital content (1.1); evaluating them (1.2); and managing them (1.3).

We previously mentioned that social capital plays both a bridging and bonding role. In digital environments, communication and collaboration skills come to the forefront in order to uphold the core elements of social capital—trust, norms, and network-building. This competence area includes interaction through digital technologies (2.1), sharing (2.2), active citizenship (2.3), and collaboration (2.4). In addition to participating in interactions, sharing, and citizenship processes, netiquette (2.5)—a term derived from the combination of “network” and “etiquette”—and digital identity management (2.6) are also included as competences. Netiquette refers to a set of rules and manners for using the internet as a tool for communication or data exchange, practiced or advocated by a group of people [6].

Being a digital citizen involves not only accessing information and data (as a reader) but also producing them and creating digital content (as a writer). This competence area includes the development of digital content (3.1), its integration and refinement (3.2), copyright and licensing (3.3), and programming (3.4). In this era where generative AI tools are increasingly widespread, the importance of these competences is growing. We will discuss below what developments in AI can contribute to programming skills.

Feeling safe is a fundamental need, positioned on the second level of the hierarchy of needs. As daily activities and social participation processes become increasingly digital, this need for security is also raised in digital contexts. The DigComp area on safety includes protecting devices (4.1), protecting personal data and privacy (4.2), safeguarding health and well-being (4.3), and protecting the environment (4.4). While AI tools can serve benevolent purposes, they can also be used to develop malicious software, leak information, and commit identity theft. This makes it all the more important to focus on the safety competence area. We will return to the importance of our safety skills under the topic of AI-assisted fraud.

The fifth competence area in DigComp encompasses the ability to solve problems encountered in the digital world. These problems may be technical issues (5.1), such as a computer not working or failing to open properly. Identifying digital needs and technological responses (5.2) and using digital technologies creatively (5.3) also fall within this area. Identifying gaps in digital competence (5.4) can be considered a kind of insurance within the entire DigComp framework. The need for digital competences continues to grow, and the required skills are constantly evolving and diversifying with new developments. Therefore, reviewing our own competences and identifying our weaknesses is essential to maintaining up-to-date digital skills.

DigComp defines eight levels of proficiency for each of these competences. For example, an individual with a basic level in the first competence of the first area is expected to be able to identify their information needs, perform a simple search to find data, information, and content in digital environments, and identify simple personal search strategies. A person with the highest level in the same competence can generate solutions to complex problems involving many interactive factors related to browsing and searching; save and filter data, information, and digital content; and propose new ideas and processes for the field [7], [8].

DigComp provides a reference framework that is too comprehensive to be summarized here. Let’s stop here for now. We will return to the knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to AI that have been added to DigComp under the section “Emerging AI Tools and Digital Literacy.”

Twin Transition and Twin Skills

In the introduction section, we discussed how machine language has permeated our daily lives. Putting that striking description aside, the digitization of daily individual activities, operations, and processes can be defined as digital transformation. So, what is the twin transition? The twin transition is an umbrella concept that encompasses both digital and green transformation. Digital transformation refers to the process by which all tasks—regardless of sector—are supported or altered by digital technologies. Green transformation, on the other hand, refers to minimizing the environmental damage of these tasks and reducing the consumption of natural resources [9]. Addressing these two transformations together under the name twin transition is based on the idea that digital transformation will play a facilitating role in achieving green transformation [10].

In this intertwined transformation process, holding on solely to digital skills will be insufficient for a sustainable future. That’s why we must also possess green skills. Put simply, green skills are the knowledge, abilities, values, and attitudes required to live in, develop, and support a sustainable and resource-efficient society. These skills are necessary to protect environmental sustainability, reduce environmental impacts, and support economic restructuring [10].

The DigComp competences of protecting health and well-being and protecting the environment offer clues about the relationship between green and digital skills. The green digital skills we emphasize as important for the twin transition are essentially the combination of green and digital skill sets. The following list briefly outlines green skills that aim to reduce environmental impact and support sustainable economies:

- Knowledge of environmental science

- Understanding sustainability regulations and standards

- Management of waste and hazardous materials

- Knowledge of renewable energy and energy efficiency

- Environmental protection technologies

- Sustainability management

In addition to green skills, the European Union has also provided us with a reference framework called GreenComp (The European Sustainability Competence Framework), similar to DigComp but for sustainability. However, for this toolkit, we will proceed by focusing on the supportive structure of digital and green transformation and the core green skills.

Current Concepts and Risks

In this section, we will cover concepts, themes, and risks that we may encounter in the age of artificial intelligence and algorithms. Not all of these concepts are directly related to or caused by artificial intelligence. However, as emphasized in DigComp, they are listed here so you can follow current trends, themes, and concepts to “identify digital competence gaps.”

Sadfishing

"Sadfishing" refers to a behavioral tendency where individuals make exaggerated claims about emotional struggles to gain sympathy [11]. This tendency, which involves sharing exaggerated issues and/or emotional distress on social media platforms to draw attention and gain sympathy, is most commonly observed among young adults [12]. Sadfishing, which can be translated as “sorrow baiting,” is considered a manifestation of complex emotional and psychosocial dynamics. The increase in negative affect and attention-seeking behavior, combined with a perceived lack of social support, can lead individuals to engage in such online behaviors [13]. Sharing photos of IV drips in the hospital, vein access photos, or a sad selfie with a crying emoji and a caption like “I can’t believe how hard I’m struggling right now. Nothing seems to be going right for me,” are examples of sadfishing behaviors. Although these posts often aim more for attention than genuine support, they can still prompt followers to offer sympathy and encouragement [14].

To clarify the behavior of sadfishing and its negative impact on communication via social media, I’ll use another expression: Attention begging! Just as beggars may exaggerate their health or socioeconomic issues to exploit others’ compassion, those who engage in sadfishing similarly beg for attention. Just as exaggeration or fabrication of problems by beggars can desensitize others toward those with genuine needs, attention begging on social media can also cause such desensitization and distortion.

Brain Rot

Selected as Oxford's Word of the Year in 2024, “brain rot” is defined as the “supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state as a result of overconsumption of trivial or unstimulating online content” [15]. The term is widely used in connection with the negative effects of excessive consumption of short and superficial content on platforms like TikTok and YouTube Shorts, especially among Gen Z and Alpha generations.

“Brain rot,” a humorous and somewhat alarming indicator of the superficiality and shortening of digital content and the reduction of our attention spans, serves as a reminder of the importance of the DigComp competence “safeguarding health and well-being.” As digital citizens, we must prioritize our physical and mental fitness and avoid the negative effects of excessive and addictive use of digital media.

However, instead of avoiding these negative effects, you may encounter peers who treat brain rot as a kind of badge of honor. You might see your friends competing for the most screen time just like they would for high scores in computer games [16]. There’s nothing wrong with peer competition—as long as what you're competing for elevates you, not deteriorates you!

Global IQ Decline

IQ scores, a measurable indicator of intelligence levels, have begun to show a downward trend in many developed countries. This decline is considered a potential threat to our problem-solving abilities and is thought to impact our capacity to address complex and multifaceted problems such as artificial intelligence or the climate crisis. The reason this decline is taken so seriously is because average IQ scores had steadily risen over the past century (the Flynn Effect). This increase, seen as a sign of humanity becoming more intelligent and of social progress, has now stopped and even begun to reverse [17]. James Flynn, who discovered this upward trend, argues that environmental factors can influence a social group’s IQ levels [18].

Yes, it seems something has started to go wrong, and a decline in our average IQ scores has begun. After identifying the problem, it is necessary to focus on its causes. One explanation proposed is that the rise of low-skilled service jobs has made work intellectually less demanding, causing people to use their brains less. Another suggested cause is that global warming is making food less nutritious. The reason we are addressing this issue here is the assessments indicating that digital technologies, which weaken our ability to focus, may also play a role in this decline [17].

Confession Pages

Confession pages refer to pages on social networking sites or independent websites created by students, especially those in high schools and universities, to share their confessions and secrets anonymously with their communities. These pages often serve as a tool for students to share their feelings, beliefs, and problems with their social circle (other students at their school), mostly in an anonymous way [19]. The issue arises when anonymity is compromised through potential clues in posts, misunderstandings lead to tension among peers, or hate speech based on race or physical characteristics begins to circulate. In most cases, these Instagram or Facebook pages referred to as “confession pages” are run by an unknown individual. When you send a message there, you may unknowingly be handing over your privacy to a stranger.

We will discuss our meetings with high school guidance counselors in later sections, but let me remind you here: your teachers are aware of the problems created by these confession pages and are trying their best to prevent you from being negatively affected.

Online Betting

The increasing prevalence of online betting among young people is a complex issue shaped by social dynamics, the accessibility of both legal and illegal betting platforms, and the psychological impact of gambling behaviors on youth. Research indicates that adolescents are increasingly turning to online gambling platforms, particularly due to the merging of gaming and gambling and the social environments that accompany these activities. Unfortunately, online betting is notably rising among males aged 17–24. The same study also shows that regular gambling is associated with frequent and harmful use of tobacco and alcohol [20]. Measures to protect underage youth from gambling on online platforms remain insufficient, and despite legal regulations, adolescents remain vulnerable to the dangers of gambling. Additionally, young people who engage in fixed-odds betting games (mostly on sports events) online face higher risks compared to those exposed to traditional forms of gambling [21], [22].

According to the information we received during interviews with school counselors, hopelessness about the future among youth appears to be a significant factor leading them to online gambling. Young people turn to online betting channels as a way to quickly earn more money to meet needs such as clothing, treating friends, and socializing. Unfortunately, promotions for both legal and illegal betting sites come through advertisements or people around the students. In some cases, students pool every last penny they have to place a bet.

Another issue with illegal online betting is the attraction created by promises of high odds. But here’s something you must not forget: Behind these betting sites are malicious people who are skilled at exploiting human vulnerabilities. Remember, no one gives you a reward without expecting something in return. Even if you win, the amounts shown on the screen will not be transferred to your account.

AI-Assisted Fraud

Scammers who deceive people by making them believe a fabricated reality have begun adding the conveniences offered by AI tools to their arsenals. With fake chatbots, voice cloning, and “deepfake” video features enabled by AI tools, your family or friends can be imitated in highly convincing ways. In short, these tools are enabling fraudsters even further.

A recently uncovered method shows just how easily your email account information can fall into the hands of hackers. In this method, you receive a fake recovery request for your email account, and minutes later, you’re called by an AI-assisted customer service representative. During the call, they try to convince you by sharing information claiming that others have accessed your account. To protect ourselves from such traps, we must stay updated on new trends and the capabilities of AI tools—and maintain a skeptical mindset [23], [24].

Risks Faced by High School Youth

Since our goal is to prepare young people for the age of artificial intelligence with the support of young leaders, we met with a group of school counselors to understand the current concerns and problems of high school students. From them, we learned about the issues you face and the problems arising from the digital world. In these discussions, privacy issues—sometimes even involving sexually explicit content—digital addiction, and lack of self-control emerged prominently. Additionally, there is the issue of “rented accounts”, which concerns not only high school students but everyone. Let's go through these one by one.

Digital technologies are transforming how we interact, socialize, and build social capital. Perhaps the most important but also the most overlooked aspect of this transformation is the permanence of the traces left by these interactions. These traces can potentially outlast a human lifetime. Known as digital footprints, these traces can be defined as the total of all the data left behind both knowingly (i.e., by intentionally sharing) and unknowingly (i.e., processed and recorded by algorithms) while using digital services [25].

We are constantly producing and leaving behind these traces. Avoiding this entirely is nearly impossible. Therefore, we must carefully choose what we leave behind. This often-ignored permanence can threaten young people’s privacy. Photos that are sexually suggestive and shared based on mutual trust among friends can circulate among students. In worse scenarios, such photos can fall into the hands of online predators and be used as blackmail, putting students in more difficult situations. These photos don’t even need to be explicit to harm your privacy. In some cases, even photos shared by your families can be used as blackmail material against you.

It may sound overly paranoid, but we still need to issue this warning: With generative AI tools, both “deepfake” videos and entirely AI-generated videos can be created. The realism of such fake or generated videos is directly proportional to the quality of the data provided to these tools. The more publicly accessible and high-resolution photos and videos of you exist online, the greater the likelihood of someone creating a fake video featuring you. This alone should remind you to reassess what you share publicly!

Another major issue is digital addiction. In secondary education, addiction to digital games, social media, and even adult dating sites in upper grades is becoming more common. Returning to DigComp, we must again highlight the competence of safeguarding health and well-being (4.3) within the safety area. You can find tips on what you can do before needing professional support for digital addiction in the next section. We also produced an animated short film on digital addiction as part of the Safe-You project. You can watch it here.

The issue of rented accounts is not limited to young people—it’s a threat to anyone willing to take risks to make easy money. Although renting out bank accounts—opened in a person’s name and using their national ID number—is not directly defined as a crime, if the account is used in fraudulent schemes, money laundering, or illegal betting, the account holder can become a criminal. Individuals who promote this, often through social media, lure victims with daily earnings of 500–1000₺. These accounts are then used to transfer funds for illegal betting sites, transfer money obtained through fraud, or launder money [26]. There is even a case of a shoe shiner being prosecuted and facing up to 180 years in prison for renting out his account [27].

Yes, on the surface, it may seem like an easy way to make some pocket money—and you may be right. But just as we said in the AI-assisted fraud section: No one gives you money or rewards for nothing, without expecting something in return!

Remember, you are now on the path to entering young adulthood, and in a sense, you will be the one taking the wheel on your life journey. That’s why self-control is extremely important! And self-control requires awareness and preparation.

Emerging AI Tools and Digital Literacy

To benefit from the opportunities offered by digital transformation, the first requirement is to have access to these services. We have largely fulfilled this need. Almost all of us have smartphones that can access high-speed internet via mobile infrastructure. The second requirement is being able to use, protect, and troubleshoot these devices. As we noted above, DigComp already addresses these competencies. Especially with the release of chatbots and generative AI tools for free use starting at the end of 2022, the importance of these competencies has become even more apparent. The gap between those who are digitally competent and those who are not may widen rapidly through the effective use of AI tools. To not miss the train, we need to update our digital competence set. That’s essentially what we’re trying to do here—at least, we’re trying to plant the seeds. It’s your curiosity that will help these seeds sprout and take root!

Let’s start by breaking the spell a little. Let’s try to understand how these seemingly miraculous AI tools actually work. Because if we understand how they work, we can also identify where they might fail and to what extent we can rely on them at different stages.

Large Language Models (LLMs)

Although we often refer to these services as artificial intelligence tools, what enables them to function and forms their foundation are large language models. Known as LLMs, these models are built on models that have been pre-trained using deep learning techniques with vast amounts of data. These models, made up of a neural network containing an encoder and a decoder with self-attention mechanisms, can derive meaning from a text and understand the relationships between words and expressions within it [28]. However, an important point must be noted: LLMs do not understand the meaning of words as humans do. They tokenize text and, based on extensive training data, predict the most likely next word.

As of 2025, the most current and advanced large language models (which, as mentioned earlier, we commonly refer to as artificial intelligence) and their features can be listed as follows [29].

| Model Name | Developer | Multimodal | Reasoning | Access Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | OpenAI | Yes | No | Chatbot and API |

| o3 and o1 | OpenAI | No | Yes | Chatbot and API |

| Gemini | Yes | No | Chatbot and API | |

| Gemma | No | No | Open source | |

| Llama | Meta | No | No | Chatbot and open source |

| R1 | DeepSeek | No | Yes | Chatbot, API, and open source |

| V3 | DeepSeek | No | No | Chatbot, API, and open source |

| Claude | Anthropic | Yes | Yes | Chatbot and API |

| Command | Cohere | No | No | API |

| Nova | Amazon | Yes | No | API |

| Large 2 | Mistral AI | Yes | No | Chatbot and API |

| Qwen | Alibaba Cloud | Yes | No | Chatbot, API, and open source |

| Phi | Microsoft | No | No | Open source |

| Grok | xAI | No | Yes | Chatbot and open source |

The fact that a model is multimodal means that it can process not only text but also audio and visual inputs. The reasoning feature, on the other hand, refers to the way these models generate responses by following a certain path or logic.

Let’s also define the other terms mentioned in the table to avoid any confusion. API (Application Programming Interface) refers to an interface that allows two different programs to communicate and work together. In the simplest terms, a model with API access can be integrated into a program you develop yourself. The term open source means that a piece of software is released in a way that allows it to be used, examined, modified, and distributed for any purpose.

Now, let’s return to our topic. As we’ve seen, there are currently dozens of different large language models available—most of them free to access. You’ve probably heard of, or even used, at least a few of them. But how do these tools produce such realistic responses, which seem as if they were written by a human, in such a short time? The answer is actually: us. All the information we’ve produced over the years, every book published, every article written, and every news story printed has made it possible for these models to generate such high-quality responses. As mentioned above, they do not understand words the way we do—they make predictions by analyzing how we combine words.

The accumulation of knowledge we have produced over centuries—and have begun storing digitally since the last century (remember the 1s and 0s we mentioned at the very beginning)—has become accessible to everyone via the internet since the 1990s. This is what made large language models possible. These models were trained using the massive amount of publicly accessible data on the internet. So how were they trained? With deep learning—a method of machine learning!

Deep Learning

Large language models owe their capabilities to deep learning processes. Deep learning is a method that teaches computers to process data in a way inspired by the human brain. While the human brain learns and processes information using millions of interconnected neurons working together, deep learning mimics this model using artificial neurons called nodes, which process data through mathematical computations. Artificial neural networks in deep learning consist of multiple layers of artificial neurons that work together to solve complex problems [30]. Deep learning, as a method of machine learning, is implemented by using a dataset to train a model.

Large language models are trained using the deep learning method. However, their training and development are not limited to that. Every action we perform using these tools, every message we send, and every piece of feedback we provide plays a role in their development.

Let’s also touch on other concepts you might hear while using or discussing these tools.

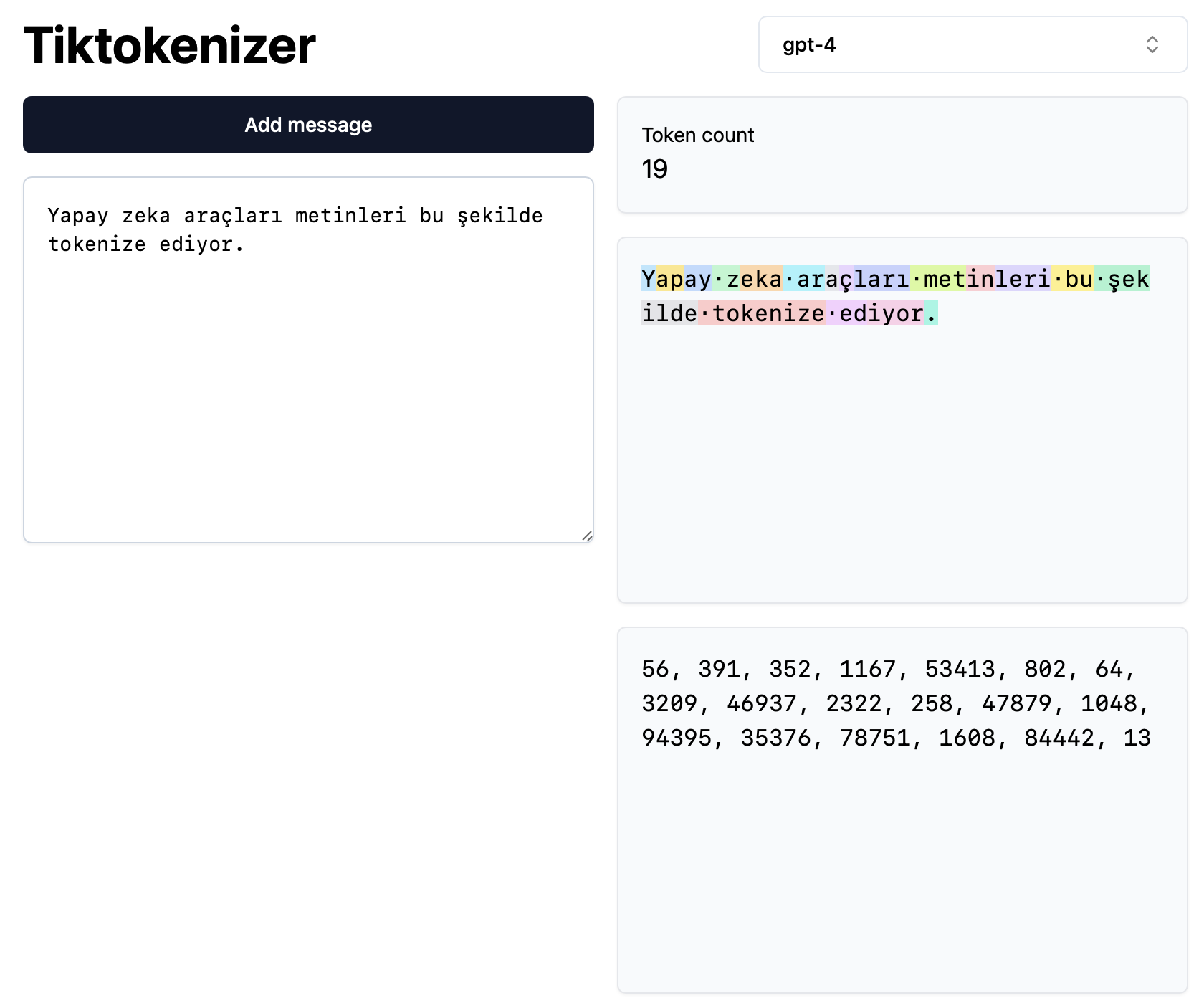

Tokenization

Before a text can be processed, it needs to be converted into a numerical format. This process, called tokenization, involves matching words, subwords, suffixes, or characters with unique numerical identifiers [31]. Most of today’s language models have used Common Crawl—a free, open web-crawled data repository that includes 250 billion web pages over an 18-year span—as part of their training dataset. In other words, during the deep learning process, a training dataset is first selected, and after it is filtered and cleaned, it is tokenized.

To understand what tokenizing is like, you can follow this link: https://tiktokenizer.vercel.app

Even having a surface-level understanding of how these tools work reminds us what to pay attention to when using them. Still, to be more explanatory, we will now share with you some of the knowledge, attitudes, and skills listed in DigComp related to AI tools.

Examples from DigComp

Digital technologies are rapidly evolving. The number and capabilities of services offered through these technologies are also increasing. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp) is periodically updated and expanded with new examples to keep up with this trend. We mentioned that the current version is DigComp 2.2. Now, let’s list the knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to AI tools included in this latest version:

- Being aware that search engines, social media, and content platforms often use AI algorithms to generate personalized responses for individual users

- Being aware that AI algorithms typically operate in ways that are not visible or easily understandable to users

- Knowing that the term “deepfake” refers to images, videos, or audio recordings of events or people created by AI, and that it may be impossible to distinguish them from real ones

- Being aware that AI algorithms may not be configured solely to provide the information a user wants, and that they may also highlight commercial or political messages

- Being aware that the data AI relies on may contain biases

- Being aware that most AI systems are developed using English texts, and that this may result in less consistent outcomes in non-English languages

- Being able to recognize that some AI algorithms may create “echo chambers” or “filter bubbles” that reinforce existing viewpoints in digital environments

- Being aware that many digital technologies and applications use sensors that generate large amounts of data—including personal data—which can be used to train AI systems

- Being able to detect signs indicating whether one is communicating with a human or an AI-based conversational agent

- Being able to interact with AI tools and provide feedback to influence future suggestions (e.g., to receive more recommendations about similar films previously liked)

- Being aware that anything publicly shared online (e.g., images, videos, audio) can be used to train AI systems

- Knowing that AI is neither inherently good nor bad

- Being aware that AI systems collect and process different types of user data (e.g., personal data, behavioral data, and contextual data) to create user profiles, and knowing how to change application or device settings to prevent or control the collection and analysis of this data

- Knowing that AI systems can automatically generate texts, news, essays, tweets, songs, and images using existing digital content—and that it may be difficult to distinguish such content from human-created works

- Being able to weigh the benefits and risks before allowing third parties to process personal data

- Being aware that processes like training AI or generating cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are resource-intensive in terms of data and computing power, and that these processes can consume large amounts of energy and have significant environmental impacts

- Being aware that AI is a product of human intelligence and decisions

- Being aware that the development and impact of AI are still highly uncertain

- Being aware that AI systems such as voice assistants and chatbots that rely on users’ personal data may collect and process this data excessively

- Having the tendency to continue learning, self-educating, and becoming informed about AI

These are the AI-related expectations DigComp sets for us to be digital citizens in the digital age. You already possess many of these qualities. However, we still need to regularly review our shortcomings—because these tools are constantly evolving, bringing new opportunities along with new risks.

Since the beginning, we've been talking about being digitally literate in the age of AI and algorithms. Now, we’ll touch on two additional literacies that we can integrate into our overarching concept of digital literacy: algorithm literacy and digital news literacy.

Algorithm Literacy

Algorithms, which are prevalent in digital media, influence content curation and user experiences. "Algorithm literacy" is defined as the ability to understand and critically evaluate algorithmically made decisions. We can integrate this skill into digital literacy instead of treating it as a separate competence [34].

Here are some expectations for becoming algorithmically literate [35]:

- Being able to change the default algorithmic settings in social networks and search engines

- Being able to alter algorithmic outputs

- Being able to compare the outcomes of different algorithmic decisions

- Being able to apply strategies that protect privacy

In another European Union project, algorithm literacy was summarized in ten points [36]:

- Algorithms are created by humans: They are not mysterious or sudden forces.

- Not all algorithms are the same: There are ranking, recommendation, and prediction algorithms.

- We are all under algorithmic influence!

- Not everything recommended is true: The first search result or recommended content is not always the most relevant.

- Algorithms and fake news sometimes form dangerous relationships!

- Information wars can destabilize democracies: Online propaganda that exploits algorithmic features is becoming more widespread.

- Algorithms are highly profitable: Their primary goal is to capture our attention and keep us online as long as possible.

- A filter bubble is cozy, but lacks fresh air: Recommendation algorithms tend to narrow our horizons by showing content aligned with our tastes and views.

- Algorithms are valuable for journalists too: When used properly, they are interesting tools for identifying public trends and reporting on “online life.”

- It is possible to act rather than just cope: Governments, civil society, and individual citizens can reduce the influence of algorithms on information and use them to fight disinformation.

Algorithms can passively spread misinformation and misleading content, and they may play a role in the wide distribution of disinformation. Due to how these algorithms are designed, they are also believed to potentially create new biases and reinforce existing beliefs, making critical thinking more difficult. This reminds us that alongside algorithm literacy, we should also emphasize digital news literacy.

Digital News Literacy

Nowadays, the news that shapes our agendas, makes us happy, sad, angry, or affected in some way, is accessed digitally. For this reason, we must combine our media literacy skills with digital literacy. Yes, we’ve used the term “literacy” quite a bit—think of digital literacy as the main category, and algorithm literacy, media literacy, and digital news literacy as its subcategories.

Let’s now look at digital news literacy. Digital news literacy encompasses a set of skills that enable individuals to effectively find, evaluate, create, and communicate information in various formats, particularly in the context of news. It serves as a critical skill set for navigating the complexities of the modern information environment without getting lost.

In a way, digital news literacy reflects your ability to evaluate a piece of news encountered online. And making this evaluation is not always easy. To distinguish facts from fake news, we need specific skills. These skills can be summarized as navigating different sources and social media, evaluating the news encountered or received, verifying its accuracy, participating and sharing only after confirming its truth, and having general knowledge about the media industry.

Recommendations for Keeping Both the Environment and Yourself Healthy

In this section, we will compile and summarize the examples, suggestions, and skills mentioned above under different headings. In an age where AI tools are widespread and our daily routines—such as communication, accessing information, and entertainment—are shaped by algorithms, we must always stay alert to remain digitally literate. And to stay alert, we also need to stay healthy. Let’s begin with the advice of Gazi Mustafa Kemal Atatürk: A sound mind is in a sound body!

Yes, digital technologies make our lives easier. With urbanization, our daily physical activity has decreased. We no longer even need to go to the market to meet our basic needs like food and drink. Additionally, the fact that most of our daily routines—including communicating with friends—are carried out through digital tools significantly affects our health, both physiologically and psychologically. For this reason, let’s start with suggestions for protecting our health. Then, we’ll complete the section with advice about AI and algorithms and actions we can take for our environment.

Track Your Screen Time

With the widespread availability of mobile internet, smartphones have begun to compete with televisions and computers, which have held our gaze for over 40 years. Now, we’re constantly staring at a smaller, closer, and more demanding screen. The people who create the content and code the algorithms on the other side of that screen are constantly working to keep our eyes glued to it. However, constantly looking at these screens negatively affects us physiologically.

It can cause a range of physical issues, from vision problems to musculoskeletal disorders, and from headaches to risks associated with reduced physical activity—such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes. Psychologically, exposure to blue light can contribute to sleep problems, attention and concentration difficulties, anxiety, depression, and emotional desensitization. So, what can we do to protect ourselves?

- Use screen time tracking apps: Depending on your device’s operating system, you can find this feature under settings as Screen Time or Digital Wellbeing.

- Protect your eye health with the 20-20-20 rule: Every 20 minutes, look at something at least 20 meters away for 20 seconds.

- Create friction: Set limits for apps you open unconsciously and use for minutes on end, or move them to a different location on your device.

- Activate blue light filters on your devices: Blue light disrupts our circadian rhythm—our biological clock—leading to sleeplessness and poor-quality sleep. Using this feature helps filter out some of the blue light emitted by screens.

- Pay attention to your posture and sitting position: Try not to look at your smart devices from too close a distance. Maintain at least one arm’s length between you and the screen.

- Incorporate exercise into your life—not just for eye health, but for your overall well-being: Don’t avoid stairs, and give up the elevator; remember, that’s also a form of exercise.

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule: To achieve this, try to avoid screen exposure for at least one hour before going to bed.

Do Brain Exercises

In a time before you were born—when there were no mobile phones—we used to reach out to our friends by calling their landlines, and most people memorized the phone numbers of those they frequently talked to. Today, we might only exercise our memory for our own mobile phone number or national ID number. Our smartphones remember and remind us of everything else.

As our devices get smarter, we must keep our creative intelligence active. Otherwise, even if AI tools don’t become as intelligent as humans, at this rate, humans might only be as intelligent as AI! In other words, AI may not reach our level of intelligence, but due to a decline in our own cognitive abilities, we might approach the level of AI tools.

Even if you don’t take this dark and dystopian prediction seriously, you should still consider the suggestions below to keep your brain active and functioning for the sake of your own health. Just as we keep our physical muscles in shape by lifting weights, running, or swimming, we also need to keep our brain in shape.

- Learn games like chess or checkers. If those seem too difficult, start solving at least one or two Sudoku puzzles daily.

- Play word games.

- Install mobile brain exercise apps like Peak or Elevate on your devices.

- Try to acquire a new skill such as playing a musical instrument, learning a foreign language, or even learning to code.

For language learning, you can use apps like Duolingo, Busuu, or Babbel. To start learning to code, you can try the Mimo app.

- Go for regular walks, runs, or do sports.

- Sports that require coordination and balance—like basketball, dancing, or swimming—support cognitive development.

- Try switching the hand you use to brush your teeth or write.

- Stimulate your brain by breaking routines: for example, walk to school using a different route.

Remember how AI models are trained—by building artificial neural networks. Likewise, by gaining new skills, we form new connections and new neural networks in our brains.

Think Twice Before Sharing

While navigating the digital world, communicating, liking, or sharing, we leave behind traces. Most of the time, we aren’t even aware of the majority of these traces. Yet, there is also a substantial portion we leave intentionally. These traces, called digital footprints, are not like footprints in the sand. They are quite permanent. It’s not really possible to leave no trace at all. But being aware of the traces we leave—and especially minimizing them during this early period of your life—is very important.

- When sharing information about yourself, your family, or your friends, always think twice. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Will my future self appreciate this post?

- Could this post negatively affect the reputation of me or my loved ones in the future?

- How uncomfortable would it be if unexpected people saw this post?

- The news and posts you come across may create the illusion that “everyone thinks like me.” Be aware of filter bubbles and echo chambers. As discussed in the algorithm literacy section, being inside a filter bubble may feel good, but it lacks fresh air and alternative perspectives.

- Also, not everything shared by the people you follow is necessarily true. Therefore, before becoming part of a stream, make your own judgment by conducting your own research: check fact-checking websites.

Doğruluk Payı and Teyit.org, which are members of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), as well as the Disinformation Combat Center established by the Presidency’s Directorate of Communications, can help guide you in fact-checking. Additionally, on X (formerly Twitter), you can tag Grok under posts to prompt X’s AI model to perform a kind of fact-check. This method is especially helpful when old events from different times or regions are shared as if they are recent.

Don’t Avoid Using AI Tools

Let’s go back to DigComp: What determines whether the results of an AI system are positive or negative for society is who designs and uses the system, how, and for what purpose. In other words, this tool is neither inherently good nor bad. What we do with it matters. Therefore, we shouldn’t shy away from using these tools. Because they are still very new and rapidly evolving. The more you experience them, the more effectively you’ll be able to use them.

Moreover, time has never been more valuable than it is now. Today, it's not enough just to have the skills to complete a task using a computer. You must also complete it in the shortest time and with the least energy. That’s where your ability to use AI tools becomes crucial. So how can we use AI tools without creating ethical problems? Here's a short—and likely incomplete—list:

- You all currently face a major challenge: the university entrance exam (YKS). While preparing for it, you can learn difficult questions with the help of AI tools. Type the question and ask, “Explain to me step by step how to solve this question,” and solve it together, for example, with ChatGPT.

- While learning a foreign language, you can use these tools for translation, pronunciation correction, and practicing both written and spoken skills.

- You can use AI tools to provide accessibility support.

- You can get help from these tools to visualize the data you’ve collected for your homework.

- You can also benefit from these tools for content summarization and report generation—but don’t forget that any summaries and reports obtained should always be reviewed. For instance, use these features for a quick review before an exam.

- You can use these tools to check the accuracy of news or social media content and to prevent the spread of misinformation. Remember, we previously mentioned Grok for fact-checking.

- You can use text-to-speech, image, and video features to create entertaining and informative content. However, while these features may not cost us money directly, they do have environmental impacts. So don’t use them unnecessarily.

- We already said you can use these tools while learning a foreign language. Similarly, they can be very helpful when learning a programming language. These tools can provide code examples, generate routine code for you, find and explain errors in your code, and support you with educational content in ways you can’t imagine. All you need is curiosity and a willingness to try!

Be Careful When Using AI Tools

Yes, we should use these tools. But there are some things we need to keep in mind while doing so. In fact, we discussed this in detail under the Large Language Models section. The datasets on which these tools are trained can be very influential. If certain people, events, or situations are missing from the training data—or represented inaccurately or inadequately—the model may produce misleading or incorrect results.

The first thing we should mention is the messages or prompts we send to these tools. There's even a new engineering discipline developed to improve the quality of these prompts: prompt engineering. This emerging field focuses on optimizing the inputs provided to AI tools for more efficient and effective use. Developing yourself in this area can help you get more accurate and consistent results while also minimizing the potential environmental impact by reducing the number of prompts needed. Consider the following tips to create higher-quality prompts [37], [38]:

- Start simple: Begin with simple prompts and gradually add more context or elements for better results. Specificity, simplicity, and conciseness usually lead to better outcomes.

- Be specific: Clearly define the task you want the AI to perform. The more detailed and descriptive your prompt is, the better the results will be.

- Avoid ambiguity: Being specific and direct generally yields better results.

- Use the latest model: As we mentioned in the section on large language models, these tools are updated regularly. Using the most current version will directly impact the quality of the results you obtain.

- Place your instructions at the beginning of your prompt and use ### or """ to separate the instruction from the context.

- Be as detailed and descriptive as possible regarding the desired context, result, length, format, style, etc.

- Demonstrate the expected output format with examples.

- Minimize vague and unclear expressions.

- Instead of saying “don’t do this,” try framing your instructions as “do this or these.”

- Use polite language when interacting with AI tools: Think of these models as being similar to children who are still learning. Consider that they might pick up on your tone, and express your requests as politely as possible.

Prompt engineering helps us reach the desired result more quickly and with less computing power. It might sound surprising, but this is actually beneficial for the environment as well. Just like every Google search, each message sent to an AI tool leaves a kind of carbon footprint. As environmentally conscious young people with green digital skills, you should carry this responsibility with you. Here's what we can do to help:

- Try to avoid typos when interacting with AI tools: As we discussed in the tokenization section, even an extra space in your message can cause it to be tokenized differently and thus produce a different result.

- Interact with AI tools only as needed, and avoid unnecessary exchanges.

- Remember that these models may collect and process more personal data than necessary.

- Always keep in mind that training AI models—or even generating responses—can be computationally intensive, leading to high energy consumption and significant environmental impact.

Keep Asking Questions and Keep Exploring

In a way, AI models are black boxes. We don’t fully know what’s inside or exactly how they work! This is true—even to some extent—for the most skilled computer programmers. For the rest of us, the mysterious and magical aspect is even greater. What can help dispel this mystery and allow us to use these tools more effectively is being digitally literate and constantly updating our digital competencies!

This is where we conclude, but this is not the end of the journey. Keep asking questions, keep exploring, keep investigating. Always doubt before believing, and make an effort to verify.

Self-Evaluation Test

You've reached the end of the toolkit. But how much do you remember? You can find out by completing the test below.